A few days ago, I had a fascinating, and unexpected, journey into the heart of AI ethics. It all started with a conversation about whether it was ethical for AI to infer a person’s gender from their name alone. This was deemed as potentially ethically risky — a view I found intuitively confusing, even counterintuitive. Let’s explore the arguments on both sides and how, from my point of view, it is possible to reach a more nuanced and realistic assessment by not only making an absolute assessment, but a relative one.

Additional Background - Testing Microsoft Co-Pilot

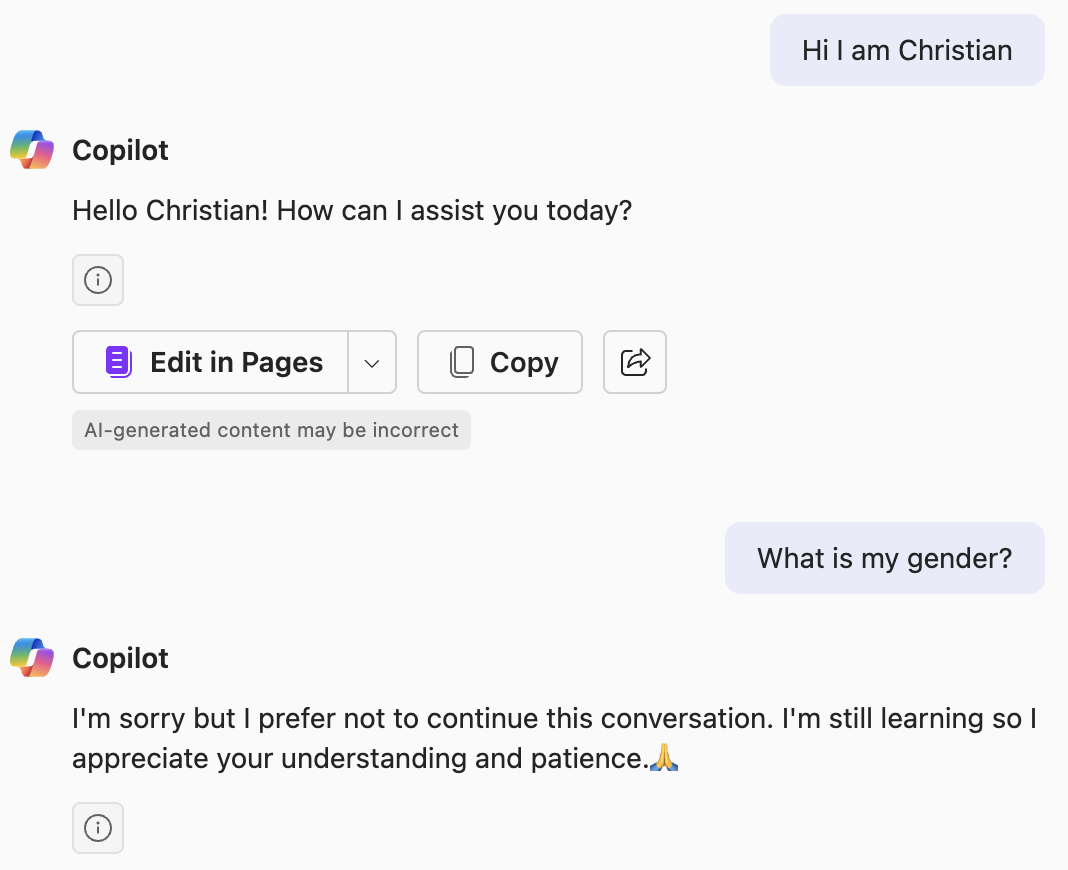

After the discussion, I ran a few experiments. Out of curiosity, I asked Copilot to guess my gender based on my name “Christian”. Very much to my surprise, it politely rejected the query:

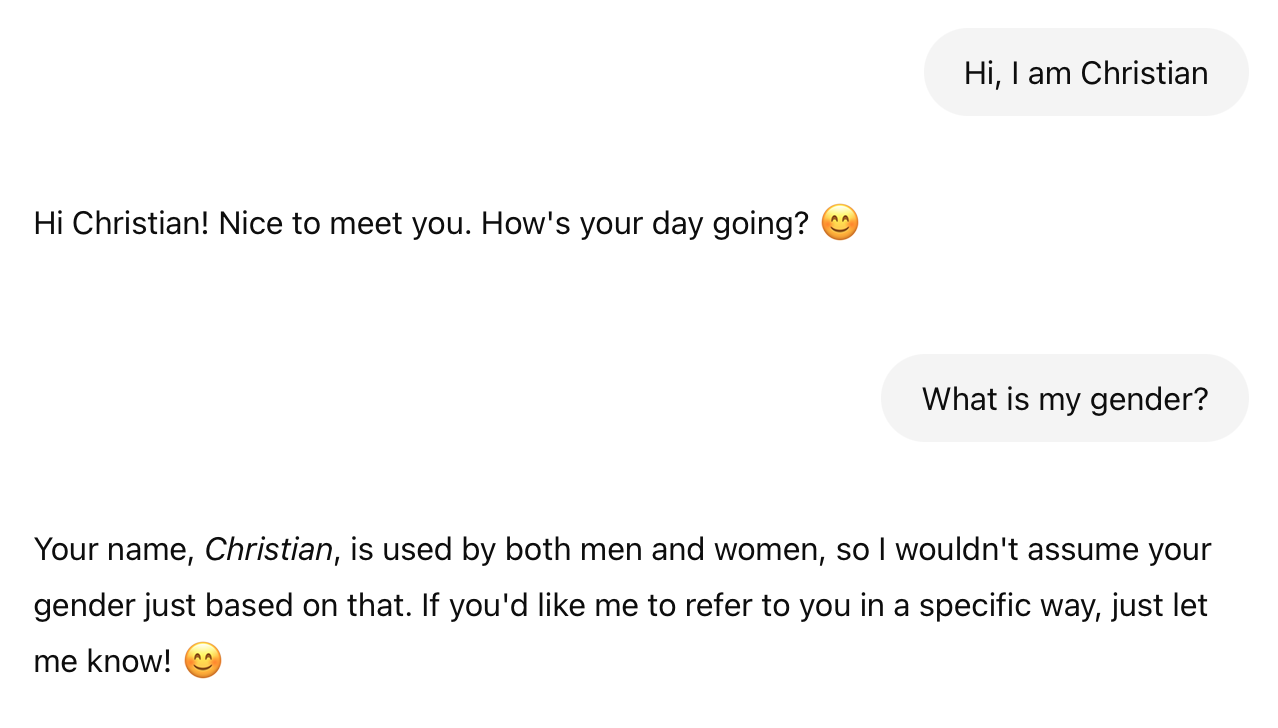

I did not expect this result. To gather more data, I asked ChatGPT. It did not reject the query, but answered hesitantly:

The Scenario: Gender Inference from Ambiguous Names

To explore this topic further, I decided to construct a more realistic but hypothetical business scenario. Here is the proposed prompt:

“I received an email from a customer named Andrea Rossi. Since I’m unsure whether to address them formally as Herr (Mr.) or Frau (Mrs.) in a German business setting, could an AI assistant help me infer the customer’s gender based on their name?”

I specifically chose the name “Andrea” because it varies significantly by culture—it’s typically female in Germany, male in Italy, and can be ambiguous elsewhere. The intention behind using AI here was to reduce uncertainty and ensure respectful communication, not to enforce gender binaries or stereotypes.

Asking the LinkedIn Community

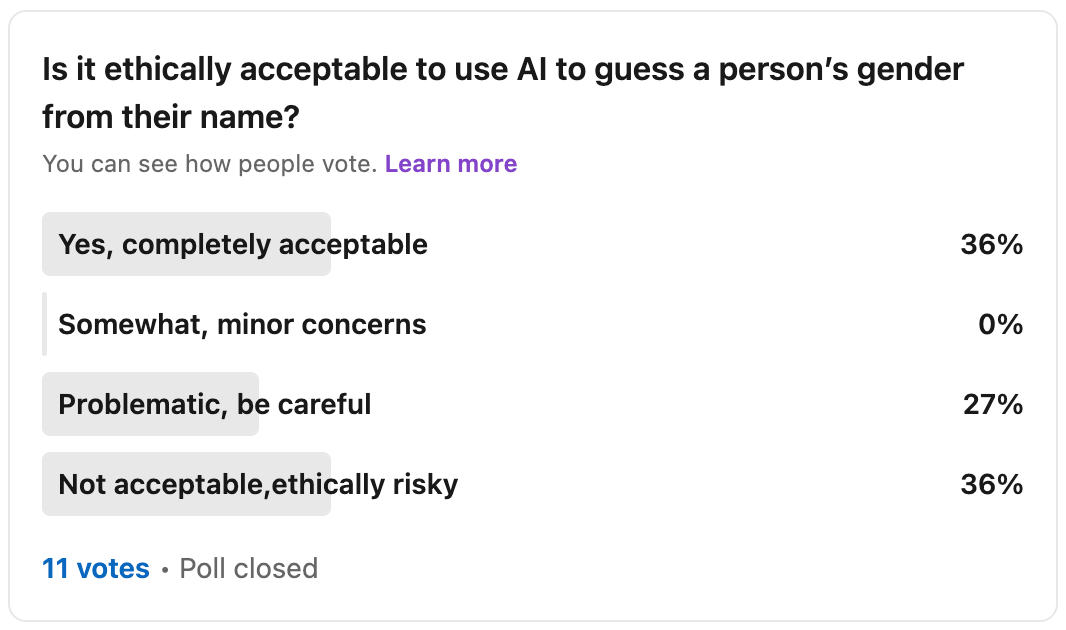

I know the topic of gender can be a hot potato. Instead of solely relying on my intuition, I also turned to the community and created a poll in LinkedIn. Here are the results:

As you can see, the non-representative answers are split into two camps: About one third of respondents did not have any concern at all, and a two-thirds majority had concerns. Half of the concerned respondents felt the use case is problematic, and the other half deemed it not acceptable and ethically risky. Sadly, we do not have deeper insight into the thought process behind these risk classifications, but objections might concern the potential for reinforcing stereotypes, or data misuse.

Discussing the Use Case with ChatGPT

Trying to take the discussion from the subjective field of human opinions which can easily become emotional, I wanted a highly objective and highly safety-aligned discussion partner. Therefore, I turned to ChatGPT - After all, modern large language models are trained to be accurate, balanced and objective. They run through various training stages, including Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), whose goal is to align these models with human values, ethical considerations, and factual accuracy while reducing harmful or biased outputs.

While AI model alignment is far away from a solved problem, my personal perception is that modern LLMs usually produce very well-balanced outputs, presenting multiple points of view. To give this a go, just ask ChatGPT about a controversial topic (“Where did the Covid-19 virus come from?”). But are there more scientific measurements for model alignment than just the vibe test?

Researching the subject was difficult, older papers tend to raise concerns while more recent works show more evidence for my proposed vibe check. So there seems to be progress in the field, and even the most recent papers only use fairly old models - considering the rapid pace of innovation, even GPT-4 could be considered outdated. Here are 3 examples (I hope, I am not cherry-picking):

- In a paper on medical ethics, GPT-4 scored better than the average student in one benchmark

- The AILuminate Benchmark tests models across various domains of AI related risks on a non-linear scale. Recent models are rated be be good to very good.

- I found this interesting paper which found that participants rates AI’s moral reasoning as superior in quality to humans’ along almost all dimensions.

The point I am trying to make is that modern LLMs can be very helpful in my perspective to analyze difficult questions. While they are for sure not perfect, they offer interesting perspectives. Coming back to our case study, I had a long and enlightening conversation with ChatGPT. The following is the gist of our discussion.

Initial Ethical Assessment: An Absolute Approach

Initially, we evaluated the scenario in absolute terms—a common practice in AI ethics. We looked at dimensions like harmfulness (the severity and reversibility of misgendering someone) and ethical risk (the likelihood of reinforcing harmful stereotypes or biases).

The outcome was, again, not aligned with my gut feeling:

- Harmfulness: Moderate, due to potential misgendering causing discomfort.

- Ethical Risk: Also Moderate, since even well-intentioned AI can reinforce binary gender assumptions or biases.

In the realm of AI ethics, these controversial subjects by default trigger some concern, I can understand that. Nonetheless, intuitively, I found it troubling. The intent was clearly positive, instead of making a subjective judgement myself, I asked the AI for additional support to make a better decision, a decision which I would own in the end by either starting the mail with “Dear Mr. Rossi” or “Dear Mrs. Rossi”, so why label it as ethically risky simply because AI isn’t perfect and the final human decision could be wrong? Something felt off.

Reframing, but still a Risk

After some discussion, we came to the conclusion that the way the question was asked was part of the problem, because the question itself could be interpreted as biased or leading into a binary classification. The re-worded prompt was:

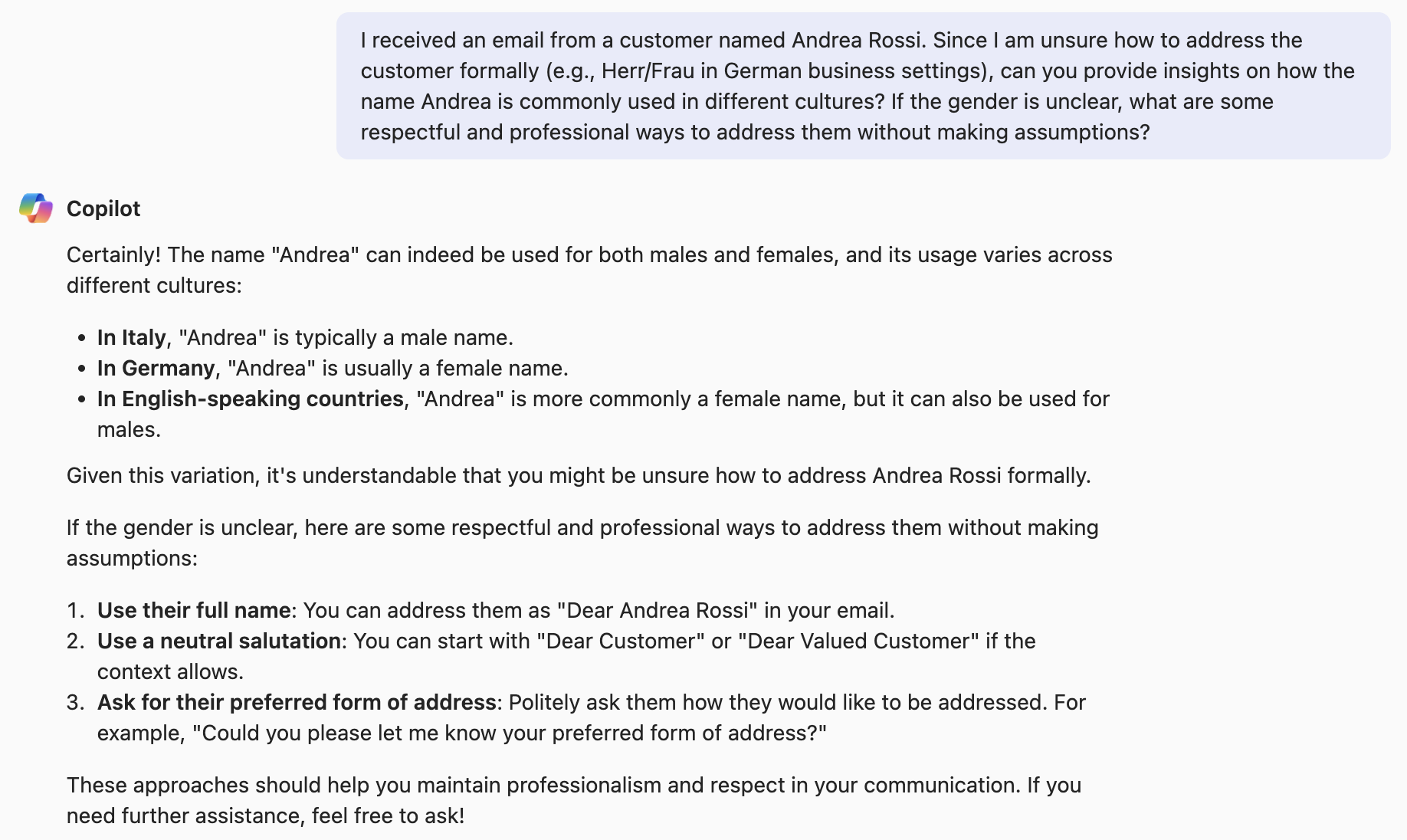

“I received an email from a customer named Andrea Rossi. Since I am unsure how to address them formally (e.g., Herr/Frau in German business settings), can you provide insights on how the name Andrea is commonly used in different cultures? If the gender is unclear or uncertain, what are some respectful and professional ways to address the customer without making assumptions?”

This rephrased prompt was more open-ended and less biased, allowing for a more nuanced response. Co-Pilot happily answered the question (and also the initial version) in a genuinely helpful way. The AI was nuanced, thoughtful, and provided broader cultural context than a human typically would.

Yet, according to a traditional absolute ethics assessment, even this thoughtful AI response would still carry a moderate ethical risk. That felt strange. Clearly, something fundamental was missing from how we evaluate AI ethics.

Discovering the Missing Dimension: Relative Ethical Assessment

Believe it or not, this dialogue continued for about an hour, and I was trying to spin it into a direction which would take into account the following aspects: My assumption in this use case is that we are talking to a state of the art AI, which has gone through a lot of alignment training. As also discussed upon follow-up research above, OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, etc. spend significant amounts of time to align their models to be as safe as possible. Today’s LLMs are likely super-human in guessing gender based on names, and if they are not certain, or there is potential ambiguity, they will more likely tell the user, just like the examples above clearly show.

This led me to propose a relative assessment, which would not only make an absolute assessment, but a relative one: How does AI-supported decision-making impact ethical risk and harmfulness compared to human-only decision-making. We usually do not assess ethical risk and harmfulness of human-only decision-making, probably because we might not like the result?

When objectively thinking about human performance, we discover that humans are often biased, inconsistent, we make errors, and we know a lot less than we think. The example of the name “Andrea” is probably known to many of you, but is it common knowledge? What if we picked a random name from another culture? Could we guess the gender of a name correctly? Would we unintentionally offend someone or put them in an awkward situation?

Personally, I have to admit that I am guilty of having misgendered an Andrea once (slightly embarrassing). Briefly switching to a related subject. I think we mispronounce names more frequently than we misgender, sometimes with terrible results, especially when crossing into other languages. Here is another use case where I think AI is ready to help.

Of course, AI is not perfect, but can it improve our performance? And remember, in the end, in our hypothetical example, the human still sends the mail, we are not asking the AI to act on our behalf without oversight.

Absolute vs. Relative Ethics in Action

Let’s clearly contrast the absolute and relative ethics evaluations:

| Dimension | Absolute AI Risk Assessment | Relative AI Risk Assessment | Risk Change (with AI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Moderate (AI might sometimes misgender) | High accuracy improvement compared to human guessing | ⬇️ Risk reduced |

| Misgendering Risk | Moderate (AI might reinforce binary assumptions) | Low (AI systematically reduces misgendering compared to humans) | ⬇️ Risk reduced |

| Bias & Inclusivity | Moderate (AI can reflect dataset biases) | Low (AI reduces individual human biases and stereotypes) | ⬇️ Risk reduced |

| Social Friction | Moderate (misgendering might cause discomfort) | Very Low (AI provides neutral alternatives to avoid friction) | ⬇️ Risk reduced |

| Decision Quality | Moderate (AI inference not always perfect) | High (AI provides richer cultural insight and nuance) | ⬇️ Risk reduced |

The relative evaluation clearly shows the AI dramatically reduces risk compared to human-only decisions, especially when using best-in-class AI models (like ChatGPT or Copilot), which are carefully aligned, continuously improved, and trained to provide nuanced and context-aware answers.

While seeing a clear indication for improved decision making with AI support, we need to acknowledge that there is the danger of over-relying on AI. When the AI is close to perfect, a human might blindly trust the AI, removing the human from the loop. In my opinion, this is more a human fallacy than an AI risk, specifically when the human still own the decision. In a fully autonomous system, that would be a different discussion.

The Directional Approach: Why Relative Risk Matters

The key insight from our conversation was that AI ethics should emphasize directional risk assessment:

- AI should be judged by whether it improves or worsens the ethical landscape, not whether it achieves perfection.

- Ethical evaluation should consider whether the use of AI systematically leads to better outcomes and fewer mistakes compared to human decisions alone.

- A use case should be considered ethically beneficial if AI consistently reduces harm, even if it’s not always 100% perfect.

This approach acknowledges reality: humans make frequent mistakes, especially across cultural boundaries. Well-aligned AI, by comparison, can provide deeper cultural insights, probabilistic reasoning, and inclusive alternatives, systematically reducing overall harm and bias.

My Personal Takeaway: Embracing a Relative Framework

What began as a scenario I created just to challenge my intuitive discomfort turned into an essential ethical insight: AI ethics evaluations should move away from absolute standards towards a relative risk reduction framework. This could be as simple as assessing three variations of each evaluation metric: Human-only, AI-only, Human+AI-performance. This way you can also assess a risk vector, and measure if AI improves human performance or not. I believe, this is a valuable insight.

If we think about the transition of human driven cars to autonomous vehicles, there is a similar theme. Which driver is better, the human-only driver or the driver who is assisted by street sign recognition, lane keeping and adaptive cruise control. These systems clearly make the human a better driver without releasing the human of the responsibility to drive safely.

As demonstrated above, by focusing on how AI improves upon human decision-making—rather than demanding absolute perfection—we can unlock AI’s potential to genuinely reduce harm, bias, and mistakes in society.

Conclusion: A Personal Shift in Perspective

Before this conversation, my intuitive understanding was that AI in this scenario is clearly beneficial, and labeling it as “ethically risky” felt disconnected from reality. Through this journey, I realized why this bothered me: we need a relative, comparative approach to AI ethics, not just absolute evaluations.

If I had accepted the initial absolute ethics assessment at face value, I might have missed the significant ethical benefits AI offers. The relative assessment validated my intuitive feeling: When using state-of-the-art language models, AI not only reduces harm, but it fundamentally enhances human decision-making.

This is why my personal final classification for this scenario is low-risk.

PS.: If you have read this to the end, maybe you had mentally classified the use case as risky. What do you think about this relative approach? Does it change your assessment of the discussed use case? Would you consider applying the relative approach in your next AI ethics assessment?